Latest weather forecast for the World Cross-Country Championships (February 18) is sunny, 82 degrees. And that may be the most sensational statement ever made about the great old race in its 120-year history.

In most of the world, cross-country is a cold-weather sport. Unrepentantly. Cross-country proudly goes ahead when all other sports are cowering under shelter from storm or snow. In the UK, where it all began, and in Europe, championships come after the holidays, and hardy club harriers plan their training to peak for their biggest races in the bleak late winter of February and March.

The grand climax of the season each year is the world championships, typically run in the northern hemisphere’s frigid March, the thoroughbred elites fighting cold winds and floundering through mud, slush, and frozen grass. The “World Cross” has been at that time of year since its first running on March 23, 1903, in Hamilton, Scotland. Traditionally, teams are selected from each nation’s own championship two or three weeks earlier—even in the U.S. and Canada where the scholastic cross-country season wraps up in December—doubling the chances of a blizzard or downpour on one of the big days.

Why does World Athletics schedule this terrain-dependent championship in the coldest, wettest season of the year?

Foxes, Hounds, and Hares

It started when a bunch of boys at an English private school, in the fall of the year 1819, wanted a game that would replicate their father’s winter pastime of hunting foxes or hares. Merging fox and hounds with hide and seek, they devised what we call paper-chasing. They sent two runners off as “foxes” with bags of shredded paper that they dropped as “scent,” and after an interval, the “pack” followed the scent and hoped to hunt down the foxes, for what they called “the kill.” They named themselves “The Royal Shrewsbury School Hunt,” and the school’s cross-country club still proudly retains the name, racing with “RSSH” on their shirts.

The lively teens of the 1830s recorded every run in handwritten ink in what they called the Hound Books, which make fascinating and often hilarious reading. Like many runners, they liked to combine their running with fun, festivity, mischief, and sometimes maverick rebelliousness. They trespassed, they incensed farmers, they stopped mid-run to drink beer and sherry, or sometimes eat a full meal (“a substantial repast at Mother Wade’s”), and they defied Dr. Kennedy, the pompous school Principal. When he tried to ban them and confiscated their scent bag, they tore up copies of his newly-published masterwork, Kennedy’s Latin Primer, and used it for the paper trail.

The Hounds’ outings were group runs, with the whole pack collaborating in tracking the scent, and holding “all-ups” to allow the slower runners to catch up. They were not races, except at the very end, when the hound who was first to catch the foxes was awarded “the brush.” (I prefer not to know exactly what that meant.) After the mid-winter holidays, in January to March, the boys introduced real races. Staying with the horseback game, they switched from imitation hunting to imitation steeplechasing. That is, they copied their fathers’ risky old hedge-leaping horseback races from village to village, church steeple to church steeple, not hunting now, but racing. The teenage boys had no horses, so again, they foot-raced across the agricultural countryside (cross-country), scratching their legs on stubble, struggling over wet plowed land, vaulting gates, scrambling over thorn hedges, and wading through streams.

Their pattern of low-key pack runs in the fall, followed by true cross-country races from January to March, is exactly how the sport is still structured—outside North America.

Other schools quickly caught on to the new sport, most famously Rugby School, where the novelist Thomas Hughes, in his best-seller Tom Brown’s Schooldays (1857) gives a vivid account of the “Barby run…nine miles at least, and hard ground,” forcing “many a youngster to drag his legs heavily, and feel his heart beat like a hammer.” Tom and his friends get back to their dormitory “limping and shivering,” but still think “Hare-and-hounds the most delightful of games.” At Rugby, the (paper) scent was laid by “hares,” not foxes, leading to cross country runners being known still as “harriers,” which originally meant hare-hunters.

Winter Running Club

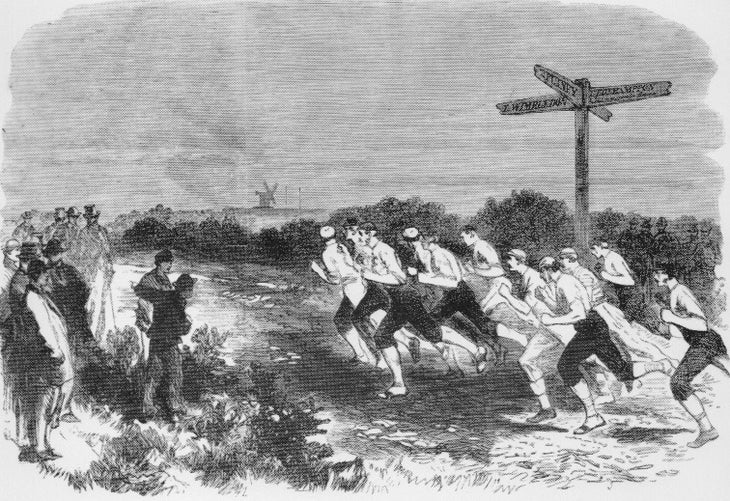

Cross-country running began its path to becoming an organized adult sport in 1867, when some members of the Thames Rowing Club in south London held steeplechase races on Wimbledon Common to keep in shape during the winter. Inspired by Tom Brown’s Schooldays, and remembering their own rambunctious running days at Shrewsbury, Rugby, or other schools, the young crew oarsmen formed themselves in 1868 into a winter club, Thames Hare and Hounds, the world’s first post-high-school running club. It still flourishes 155 years later, the members racing on the same ground, wearing the same black and white club uniform, with the black saltire or X. (I once heard an American runner describe me as “the guy with the kiss on his shirt.”)

Other clubs quickly sprang up, enough to hold an inter-club championship of England in 1876, in Epping Forest, north London. Unfortunately, they still used paper-trail to mark the course, and it all washed away in torrential rain, leaving the runners adrift. One later remembered being, “quite at sea in the forest, wandering about for hours in a frozen condition.” When he finally staggered back to race headquarters, they rubbed him with brandy. “But personally,” he recalled, “I thought internal application would be better and I snatched the glass. The next thing I remember is waking up in the Old Pavilion Music Hall.”

The sport spread. Already, running showed the strengths that make it so successful in our own time–the fun, challenge, flexibility, low cost, contact with nature, health benefits, and balance between deeply individual fulfillment and an inclusive and supportive community. In 1903, England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland (as it was then) formed the International Cross-Country Union (ICCU) and that March, held the first international championship in Scotland. Over 8.5 miles, it was won by the great Alfred Shrubb, multiple world record holder on the track.

France joined the ICCU in 1907, bringing great runners from Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia, like Alain Mimoun, who won four times. When those nations became independent, they entered their own powerful teams. Farther-away nations began to appear, South Africa in 1962 (pre-apartheid ban), New Zealand in 1965, and the USA in 1966, on the sandy racecourse of Rabat, Morocco. That was when the unknown Tracy Smith, from California and the University of Oregon, stunned the hardened Europeans by placing third.

Milers and Marathoners Meet in the Mud

The championship quickly became the world’s premier annual footrace, team and individual. It was both inclusive and elite. It thrust together the best milers and best marathoners, steeplechasers and road runners, Olympic track medalists and inspired club harriers in a single seething contest over 7.5 miles of unpredictable terrain during the off-season for track and road competitions.

The sport outgrew the old anglo-dominated ICCU, which dithered about admitting women. In 1973, it was all taken over by the international federation (now World Athletics). Cross-country, the maverick winter sport, populated by eccentric skinny people who were no good at football, became the first official world championship of running. Track and field and the marathon followed dutifully ten years later.

Different Down Under

The 2023 races, for the first time, will be down under in Australia, at Bathurst, out on the New South Wales goldfield tablelands, where the maximum recorded February temperature is 107 degrees F. It’s bushfire season. Resident wildlife includes emus, rat-kangaroos, death adders, the duck-billed platypus that blew Charles Darwin’s evolving mind when he visited in 1836, and the bare-nosed wombat, which drops its poop in perplexingly perfect cubes.

It’s going to be different.

Why Bathurst? Besides the scenic Mount Panorama overlooking the town, it is Australia’s top motor-race circuit. No cross-country course would deign to set foot on the smooth asphalt or concrete that fast cars require (a wuss sport by comparison), yet the grandstands, social facilities, hotels, and the steep grassy slope of the mountain make it a smart choice. The course description talks of a “billabong” (stagnant muddy pool, as in the song “Waltzing Matilda”), and a “boomerang” (curved wooded weapon lethally hurled by the Aboriginal people), and, more conventionally, a rough-footing hill to climb and descend, all part of the technical skills that give true cross-country its unique identity.

This year’s race in Bathurst will be highlighted by festivities for the fiftieth jubilee as a world championship. Those fifty years have seen two great changes, unforeseen in the early years: the advent of women, which has given us such icons of cross-country brilliance as Doris Brown Heritage and Tirunesh Dibaba, and East Africa’s meteoric rise to dominance, with superlative Kenyans, Ethiopians, and Ugandans at the front of every field. And this year, for the first time, the program includes masters’ championship races, bringing in serious elite runners aged up to 80 and over.

With 82 degrees of Aussie sunshine—and six-sided wombat poop—it might seem all to be very different from the romp over rain-soaked hills and wintry farms on the scent of the paper trail 204 years ago. Yet every runner will be on the grassy slope of Mount Panorama for the challenge of racing at high tempo over varied natural terrain, exactly the same challenge that so enthused those inventive schoolboys.

Roger Robinson ran the world cross-country championship for England and later New Zealand, and will race in the 80+ masters grade on February 19. He is regarded as the outstanding historical writer on running. The seminal story of cross-country’s beginnings is in his new book, Running Throughout Time: the Greatest Running Stories Ever Told (Meyer & Meyer, available through Amazon and all online outlets and bookstores).

The post Why World Cross Country Is Proudly a Winter Sport appeared first on Outside Online.