I was having an email exchange with a longtime friend a few months ago, and we got to talking about our long-ago youth—specifically, the workplace where we met, when we were both in our teens. As is often the case in these late-evening conversations, the discussion turned to the subject of who else among us has survived from that ancient era: 1974 to 1978. No, that’s not quite right: The discussion turned to who hasn’t survived: a roll call we occasionally catalogue and, now and again, update. In this case, the subject in question was that guy a couple of years older than us who worked in a different department but in the back of the same office. The dude with the cool, round-shouldered affect. Heavy drinker. Heavy shrugger. You know.

We didn’t know. And then, the next day, we did, our emails arriving in each other’s inboxes nearly simultaneously. I remember now! His name was Jimmy C—.

My one salient memory of Jimmy is the evening four of us from that office attended the world premiere of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest at the 1975 Chicago International Film Festival. Why Jimmy was part of our entourage, I have no idea. Possibly he just perked up when I announced, from the front end of the office, that I was buying tickets to this amazing event-to-be. Also probably, almost certainly, because we weren’t taking into account the existence of anyone outside of ourselves, because why would we?—we timed our arrival at the Granada Theater to coincide with the opening of the outside lobby doors for general admission.

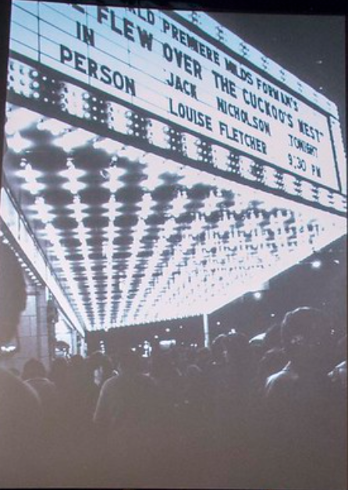

The ticket-holder line, a haphazard assemblage measuring four or six across, stretched from beneath the theater marquee to the el station a block away. The Granada, dating to the movie-theater-as-palace heyday of the 1920s, could hold 3,400. Apparently 3,396 had beaten us to the scene.

We started down the sidewalk, at least one us resigning himself to his eventual lot in the back row of the uppermost balcony, but then Jimmy did maybe the most incredible thing I’d ever seen. He stopped, said, “I think we’ve gone far enough,” and about-faced. Then he stood still, next to four or six oblivious cineastes, facing the marquee. Just like that, he was near the front of the line.

The other three of us hesitated, our incomplete prefrontal cortexes pinwheeling between the disappointing, if morally irreproachable, position under the el platform and the satisfying, if morally risible, position under the theater marquee.

Of course we chose the under-the-marquee position.

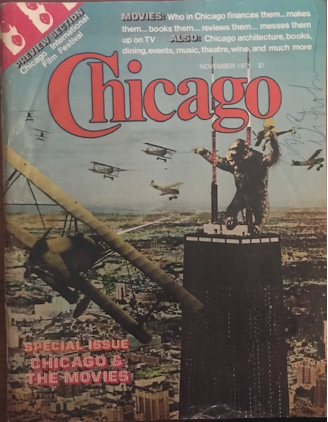

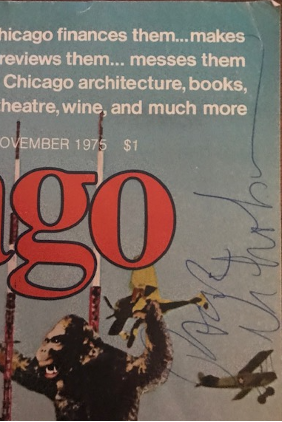

Before long the street doors opened and then the four of us were inching through the shoulder-to-shoulder mob in the lobby, and I felt several people crowding my right shoulder, and I turned in annoyance, and there was Jack Nicholson. I held out my copy of Chicago magazine, a complimentary handout at the door, and asked for his autograph, because that’s how young and stupid I was, and he noticed the accompanying glossy insert advertising the following month’s opening of Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, and he asked if he could see the insert, and I handed it over while insisting it was all his, and he said thanks and signed my magazine cover, which I recently retrieved from my childhood home, and I’d like to delude myself that by introducing him to Barry Lyndon, he said to himself, Hey, I’d like to work with this Kubrick fellow, and so he auditioned for The Shining, and therefore I made his career.

My friends and I—well, Jimmy wasn’t exactly a friend, but he was at least an in-the-moment co-conspirator, which, at that stage in the development of the prefrontal cortex, really isn’t all that different—got to watch the movie from center-left orchestra. We witnessed Randle McMurphy (played by my protégé Jack), a patient at (what was then called) an insane asylum, commit one act of defiance after another. Each transgression seemed to his fellow residents on the ward to be, one after the next, the most incredible thing they’d ever seen. McMurphy was shaking a fist at God (in the guise of Louise Fletcher, playing Nurse Ratched, the overseer of this wing of the asylum, and #5 on the American Film Institute’s list of all-time movie villains), at least until he underwent a lobotomy—a severance between the prefrontal cortex and the rest of his brain.

The world premiere of Cuckoo’s Nest was a standing-ovation success. After the final credits much of the creative team took their bows: Jack, of course; Milos Forman, the director; Michael Douglas, one of the producers; and I guess Louise Fletcher, too, since I see from the photo at the top of this essay that her name was on the marquee, promising her attendance. I can’t imagine why anyone would have thought her name would be a draw. Not that the event needed a draw. Maybe her mention on the marquee was a contractual thing, part of a studio’s Oscar campaign.

If so, that strategy worked. Four months later she won the Academy Award for Best Actress, part of the first sweep of the four major award categories since It Happened One Night forty-one years earlier—Best Film, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress (plus a bonus: Best Screenplay Adapted from Other Material by Lawrence Hauben and Bo Goldman).

Louise Fletcher died on September 23, 2022, the same day that my longtime friend and I simultaneously remembered Jimmy’s surname. A minute after our emails crossed, my friend emailed me an update he’d just discovered: Jimmy’s obituary on Legacy.com.

Both the novel and the movie adaptation of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest belonged to an artistic subgenre of the era that asked who is actually insane—the inmates of the (literal or metaphorical) asylumor the caretakers? (See the movies King of Hearts and Titicut Follies or read the novels Catch-22 and Slaughterhouse-Five, just for starters.)

Surely the post-lobotomy Randle McMurphy would have kept shuffling along the sidewalk until he had reached the el station. And then he would have about-faced and shuffled back to the lobby doors under the marquee and found his place in the back row of the uppermost balcony.

And if the four of us co-workers/co-conspirators had been a few years older, maybe we would have, too.

But maybe not. Randle McMurphy’s severance was complete. The slightly older versions of the four of us moviegoers, however, would have still possessed the intellectual capacity to make a choice. We would have known that if the line is long, the reward will be distant, but if we take a shortcut, the reward will be imminent. And then each of us would have balanced the practical against the moral through an inconceivable number of neuron connections culminating in our consciousness as an option no longer available to Randle McMurphy: a belief in the illusion of free will.