image via complaint

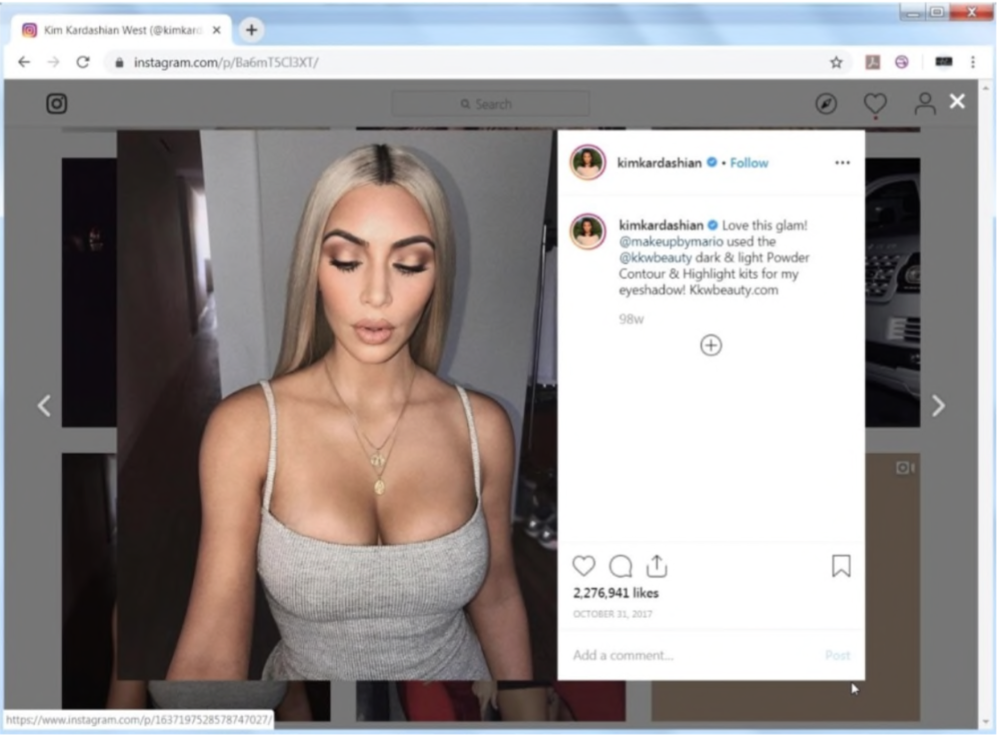

In October, Kim Kardashian accused the developers of a selfie beauty app of taking a photo that she had posted of herself to her Instagram account in October 2017 and using it in a world-wide marketing campaignto promote their service without her authorization. In her suit, Kardashian set forth a single claim common law misappropriation of the right of publicity demanded that iHandy Ltd. and Taplogic, Inc. be forced to pay damages to the tune of $10 million as a result. Now, the defendants are asking the court to toss out the case on the grounds that it is little more than baseless litigation aimed at chilling expression.

In their formal responses to Kardashians complaint filed early this month, sweetcamapp-makers iHandy and Taplogic deny or assert that they lack sufficient knowledge or information to either affirm or deny the bulk of the reality star-turned-slash-moguls claims. Beyond that, they set forth an array of defenses, arguing, among other things, that the court lacks jurisdiction over them because their principal place of business [is] in China.

More interestingly, iHandy and Taplogic claim that Kardashians right of publicity cause of action one that provides an individual with the right to control unauthorized commercial uses of his/her name, likeness, or other recognizable aspects of his/her persona is barred by the fact that it is completely preempted by the Copyright Act.

The defendants argue that in lieu of filing a copyright infringement claim against them for using a photo of her (likely because she either is not the copyright holder for the image (which appears to have been taken by someone else) or lacks a copyright registration for the photo), Kardashian asserts a common law right of publicity claim, instead. The problem with that, iHandy and Taplogic argue, is that Kardashians right of publicity claim conflicts with federal copyright law, which should be the governing law here.

(The Copyright Act provides thecreatorof a work (not the subject of the work) with certain exclusive rights, including the right to use/display that copyrighted work. As such, an individuals right to control the use of his or her likeness under a states right of publicity law can sometimes clash with a copyright owners exclusive rights in a copyrighted work. In such instances, the Copyright Act states that is it the controlling doctrine, and any common law rights, such as publicity rights, that are equivalent to copyright are preempted.)

image via complaint

Given that copyright law at its core protects creative works, such as photos, preemption makes sense here on its face. After all, the case centers on iHandy and Taplogics allegedly unauthorized use of a photo of Kim K.

However, the defendants argument in favor of looking to the Copyright Act as the governing law in this case, which would provide them with an easy win as Kardashian does not have a copyright registration for the photo (which is a prerequisite to filing an infringement suit), might fall short since the U.S. District Court for the Ninth Circuit has held that right of publicity claims are, in fact, preempted by copyright law in certain instances. Namely, they are preempted when a likeness has been captured in a copyrighted artistic visual work and the work itself is being distributed. On the other hand, they arenotpreempted when a persons likeness is used on merchandise or in advertising without their authorization.

The Ninth Circuit determined this in the right of publicity case that former NCAA athletes Patrick Maloney and Tim Judge filed in California federal court against T3Media in connection with its unauthorized sale of images depicting games in which they played. In that case, the court ultimately held that because T3Media which argued that the plaintiffs right of publicity claim was preempted by the Copyright Act distributed the photographs, rather than using those photographs on merchandise or inadvertising, its use fell within the scope of the Copyright Act, and the plaintiffs claims were preempted.

Applying that outcome to the case at hand, in which the defendants appear to be using the image of Kardashian in furtherance of an advertising campaign to promote their app (in which users upload images of themselves to edit), preemption does not seem likely.

Nonetheless, the defendants go on to claim in a subsequent defense that their use of the image of Kardashian is protected by fair use; the photo was allegedly available on a website accessible to the public; and thus, the case should be tossed out because it amounts to a Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation (SLAPP), a lawsuit centers onfree speech activities protected by the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

According to iHandy and Taplogic, Kardashian cannot demonstrate any probability of prevailing because she fails to state a claim, and any claim [she has stated] is [either] preempted by the Copyright Act [or] precluded by the First Amendment, and the case must be dismissed pursuant to California Code of Civil Procedure section 425.16, which is the states anti-SLAPP statute.

*The case is Kim Kardashian West v. iHANDY LTD., et al,2:19-CV-10877 (C.D.Cal.)